The body interacts with a three-dimensional environment (on three planes), but often we restrict our bodies by only moving in one dimension. Purposely engaging a full range of movement with conscious breath can infuse the body with much-needed, energizing oxygen and a missing vitality.

PART THREE: Learn to Move and Breathe in Rotation (Transverse Plane)

Wholeness of movement!

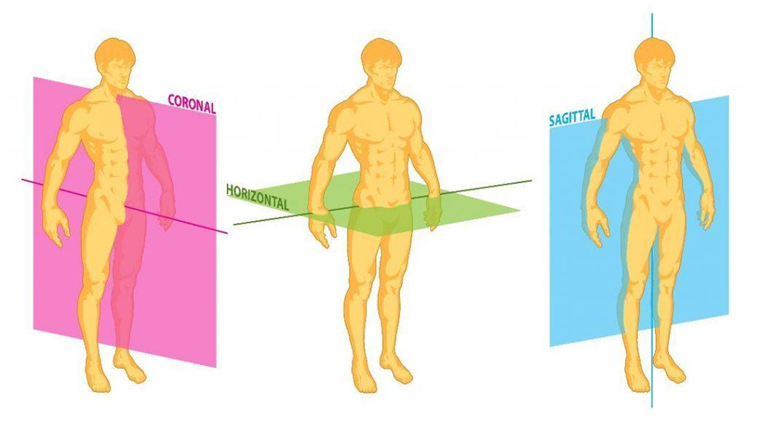

We are meant to move along three-dimensional planes of movement: turning right and left (horizontal/transverse plane), side to side (frontal/coronal plane), and forward-backward (sagittal plane). Limited and repetitive movement patterns silently unravel our attempts to live a holistic life with vitality. Conscious movement or paying attention and focusing movement in a specific direction is important. As an adult, it is easy to see that most of our movement patterns throughout the day are in the sagittal plane as we bend forward or backward. The frontal (coronal) plane movement influences our quality and ability to move to stand on one leg, enable toilet hygiene or keep our balance should we trip and our base of support narrows. But it is transverse plane that allows us to see safely what lies all around us. This month we take a look at movements of rotation or turning right and left (horizontal/transverse plane).

When trying to visualize movement in the transverse plane, think of a golf swing: the ball and socket joints of the shoulder, hip and ankles synchronistically rotate inward and outward while at the same time the thoracic spine and pelvis rotate opposite to the upper cervical spine. This allows the eyes to never lose contact with the golf ball.

How do you turn?

Just how good are you in your ability to move in the transverse plane? One quick way to assess the overall quality and quantity of rotation available in your neck, middle back, hips and ankles is to stand with your feet comfortable close together with your arms down at your side and look forward. (Figure 1) Leading with the eyes, turn the head to look over the right shoulder. No need to move into pain or try to stretch and push through to get more twist or turning. Your chin should align comfortably over the middle of your collar bone or clavicle. (Figure 2) Continue to turn to the right, allowing the both shoulders to move right. From their original starting position, the shoulders should rotate about 50˚. (Figure 3) This is a general indicator of thoracic spine mobility. As you continue to turn, the pelvis will shift to the right and rotate around to the right, about 50˚ from the original standing posture. This is also a measure of right hip outward rotation and left hip inward rotation. (Figure 4) Finishing the turn, notice how easy it is to keep the knees fairly straight or does one knee bend more than the other? Can you sense the ankles rotating or is one heel lifting? Does the inside arch of the right foot lift and the inside arch of the left foot lower to the ground? (Figure 5). Repeat the same assessment on the other side. Can you do so without excessive effort or pain? Do you hold your breath? Is there a lack of symmetry between the two sides?

Some Body Parts Are Built for the Transverse Plane

The thoracic vertebrae are skeletally designed to move in all three planes of motion allowing us to rotate, bend forward, backward, and side to side. However, thoracic side bending at the vertebral level becomes limited because of the special connection the vertebrae share with the ribs. However, this special connection promotes the ability for us to take a deep breath in and out. This rib-thoracic spine connection allows the ribs to elevate and spin or rotate, making breathing easier throughout various activity levels.

Excelling at rotation, mobility of the thoracic spine is the first segment of the spine to shut down or restrict its motion in order to preserve balance. When we lose the normal 45-60˚ of thoracic rotation due to habitually sitting in poor posture or inefficient and poor movement patterns from past traumas or injuries, the first sign is loss of range of motion in the shoulder, whether it is reaching over our head or behind our back. As the thoracic spine becomes more rounded (called kyphosis), there is another loss in our ability to see over our shoulder or check our blind spot when driving a car. Less obvious but contributing to back pain and osteoarthritis of the lumber spine or low back, is the deterioration of the normal counter-rotation of the shoulder and the pelvic girdles during walking. If the thoracic spine cannot rotate, then the rotation is shifted down into the lumbar vertebrae. Collectively, the five lumbar vertebrae have very little capacity to rotate, 8-12˚ compared to the twelve thoracic vertebrae 45-60˚.

Try A Movement Exercise

Breathing, with awareness through various planes of movement, is the only vital process that we can voluntarily control quickly and with the least amount of practice. Developing efficient movement patterns that improve the coordination of the spine, ribs, shoulder and pelvic girdles is vital not only for our breath but also for our movement quality of life. Consciously perform the following rotation-motion exploration while noticing your breath. The movement is taught standing up, but it can also be done in a chair. The result should be a fuller, deeper breath and potential for the breastbone and ribs to lift us out of a late afternoon slump or after long periods of sitting. Essential to the movement is to go slow, stay curious or open to how parts of yourself can move differently than what you have always known. Less important is how far you can turn and more about the effort that you are using. May you continue to enjoy a full, deep breath with ease, moving in all planes of motion!

Figure 1.

Stand with your feet comfortable close together with your arms down at your side and look forward.

Figure 2.

Leading with the eyes, turn the head to look over the right shoulder. Notice where your chin aligns comfortably along your collar bone or clavicle.

Figure 3.

Continue to turn allowing the shoulder girdle to rotate right.

Figure 4.

Continue to turn allowing the pelvic girdle to shift right and rotate right.

Figure 5.

Continue to turn allowing the knees to stay fairly straight. Sense the ankles rotating or the inside arch of the right foot lifts and the inside arch of the left foot lowers to the ground?