The walk of the African water carriers inspired Ruthy Alon as she created Bones for Life. She shares seeing the easy grace with which these women moved under a load, as well as reading early research on their low bone density and low fracture rates. She further indicates that she deciphered the movement skills of these women and teaches these skills within the Bones for Life program (1). In this article, we will take the basis of this inspiration and break it down into some of its current day components.

Look at the apparent ease with which the woman at left carries her load. Of course, it isn’t easy, yet studies show Luo and Kikuyu women are supremely well organized, even outperforming male U.S. soldiers with loaded rucksacks. She can carry up to 20% of her body weight on her head before she begins to need more oxygen or burn additional calories. (1)

Look at the apparent ease with which the woman at left carries her load. Of course, it isn’t easy, yet studies show Luo and Kikuyu women are supremely well organized, even outperforming male U.S. soldiers with loaded rucksacks. She can carry up to 20% of her body weight on her head before she begins to need more oxygen or burn additional calories. (1)

Carrying a Load for Free.

Just to put this in context, if you weigh 150 pounds, this means you would be carrying 30 pounds. Can you imagine balancing even 20 pounds on your head and, say, walking around the block? Much less without gasping for additional air? Scientists call the capacity to carry this weight without needing more air “carrying for free.” In fact, she may add to her load up to 50% or more of her body weight and head into town. While her “free energy” zone will have been passed, she will still carry her load at a lower metabolic cost to herself than to you or even to our beloved Army guys and gals.

Walk Like an Upside-Down Pendulum.

In the 1990s gait researchers mapped the movement of the human center of mass in space and discovered its trajectory is like that of a swinging upside-down pendulum. Instead of a curve down, it curves upward with the crest being at the point when you are completely balanced on one foot and the other foot has lifted away from the ground and is swinging forward.

In the changeover between steps, most of us will lose height faster than we gain speed with a few millisecond lurch. But loaded African women pause less in the middle of the step and in fact some women do not pause at all. Another way to say it might be that the rhythm of the walk is uninterrupted.

In the changeover between steps, most of us will lose height faster than we gain speed with a few millisecond lurch. But loaded African women pause less in the middle of the step and in fact some women do not pause at all. Another way to say it might be that the rhythm of the walk is uninterrupted.

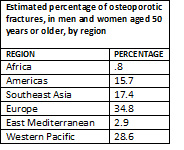

The beauty of such an efficient load bearing walk caught the attention of Ruthy Alon some years ago along with two other factoids of the time: West African women had low fracture rates (statistics still support the low fracture rates–see table below) and low bone densities (these studies need to be validated).

Many are captivated with seeing the act of carrying loads on the head. Here is YouTube Video that will complete the visual picture:

2004 Report from the World Health Organization (2)

The reason Africans have significantly lower fracture rates than Americans is likely multi-variant. Climate, diet, genes, bone geometry, daily movement requirements and movement patterns are all possible, even likely, contributors.

The research does confirm that when skeletal alignment, stability and flexibility in the curves of spine, and rhythm improve, there is less loss of energy between steps. That is, the peak moment of rest in the pendulum swing is more fully converted back into energy. You are no longer falling as you walk but remain tall and balanced.

Does Posture Influence Osteoporosis, Fracture Risk or Osteoarthritis?

The way in which bone receives its messages for health is currently understood to be through weight bearing use. Dr. Moshe Feldenkrais, a somatic pioneer whose work provided the early roots of Bones for Life® through The Feldenkrais Method®, often explained the development of systems in the following simple way. For the capacity to see to develop, light is needed. For hearing to develop, sound is needed. To develop bones, gravity is needed. Without the need to move against gravity, there is no need for a skeletal system.

Whether lifting weights, carrying water on the head down the road, or simply carrying one’s own body weight, the way in which the load is carried is important to trigger messages of health to the bones and joints. Organic beings are shaped and reshaped according to the patterns of use. In humans, patterns of use are not only influenced by geography but also by culture and family. Individual potential is activated or atrophied according to personal preferences and choices within these environments. It is agreed that walking is good for bone health. But does the way in which we stand or walk also impact the prevention of bone and joint disease?

That poor posture is a contributor to osteoporosis is widely accepted. Particularly talked about in most primers on causes and interventions for osteoporosis, standing straight is acknowledged as an antidote to the hyperkyphotic thoracic spine, more commonly referred to as an excessive hump in the upper/mid back. A retrospective study of 596 community-dwelling women found an association between this postural habit and future osteoporotic fractures. (6) Results from a study of 1,883 older adults suggest that hyperkyphotic posture is an independent marker for determining fall risk in men (4). Further, in a much smaller group of 60 women, osteoporosis and a hyperkyphotic spine and head forward posture did correlate with increased falls and demonstrably less postural control when standing quietly on a stable surface (5).

Osteoarthritis is also likely influenced by inefficient patterns of use. While the etiology of osteoarthritis is still unknown (7), studies examining possible links between the way in which a person uses their body and the formation of osteoarthritis are starting to emerge. Whether an older adult develops knee osteoarthritis has been connected to their gait pattern. (8)

Summary

Given that the way in which we stand and walk contributes to decreased fall risk and better bone and joint health, helping individuals improve in these areas has far reaching benefits. Understanding and learning the required skeletal organization and the movement through space of the upside-down pendulum to safely bear loads on the head across long distances, even though the environmental need or personal choice for such may never be activated, is a major aspect of Alon’s Bones for Life® movement protocol.

Cynthia M. Allen is a Guild Certified Feldenkrais Practitionercm and Bones for Life® Teacher/Trainer. She has a private practice in Cincinnati, Ohio. You can find out more about her and her practice at futurelifenow.com. Cynthia Allen can be reached by email at CynthiaAllen@FutureLifeNow.com.

References:

- Alon, R. Bones for Life Teachers Manual, Segment I, 117

- Heglund, N. C., Willems, P. A., Penta, M., & Cavagna, G. A. (1995). Energy-saving gait mechanics with head-supported loads. Nature, 375(6526), 52-4.

- WHO Scientific Group on the Assessment of Osteoporosis at the Primary Care Level. (2004). Summary Meeting Report. Brussels, Belgium. 5-7

- Kado, D. M., Huang, M. H., Nguyen, C. B., Barrett-Connor, E., & Greendale, G. A. (2007).Hyperkyphotic posture and risk of injurious falls in older persons: the Rancho Bernardo Study. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences, 62(6):652-7.

- Burke T. N., França, F. J., Meneses, S. R., Cardoso, V. I., Pereira, R. M., Danilevicius, C. F., & Marques, A. P. (2010). Postural control among elderly women with and without osteoporosis: Is there a difference? Sao Paulo Medical Journal, 128(4):219-24.

- Huang, M. H., Barrett-Connor, E., Greendale, G. A., & Kado, D. M. (2006). Hyperkyphotic Posture and Risk of Future Osteoporotic Fractures: The Rancho Bernardo Study. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 21(3):419–23.

- Michael, J. W., Schlüter-Brust, K. U., & Eysel, P. (2010). The epidemiology, etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International, 107(9):152-62.

- Rudolph, K., Schmitt, L., & Lewek, M. (2007) Age-related changes in strength, joint laxity, and walking patterns: are they related to knee osteoarthritis? Journal of Physical Therapy, 87, 1422-31.