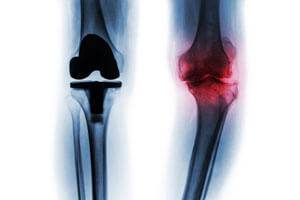

Over the last 40 years, and certainly most recently, advances in surgical techniques allow persons suffering from severe knee or hip pain to return to active lives through Total Joint Replacement (TJR). TJR is a surgical procedure in which arthritic or damaged joint surfaces are removed and replaced with an artificial joint or “prosthesis”. The prosthesis is designed to move like a healthy human joint. Most TJRs involve the hip and knee joints; however, total joint replacement can also be performed on joints in the ankle, shoulder, fingers, and elbow.

In 2003, about 652,000 total joint replacements of the knee and hip were performed by orthopedic surgeons in the U.S.1 and over 60% of them were performed on women.2 Technology is such that implant materials now accommodate both the female and male anatomy as well as being safer and more effective than their earlier counterparts. There are specialized instrumentation devices such as computer-assisted surgical monitoring systems and special x-ray equipment to ensure a well bonded fit and proper alignment of the prosthesis.

In either a Total Knee Replacement (TKR) or a Total Hip Replacement (THR), the prosthesis is made of either a strong metal alloy, (like titanium) plastic or ceramic. The prosthesis is anchored to the ends of either the femur or tibia where the diseased bone has been removed. Often it is held in place with some type of adhesive material, such as, cement. In younger people or people who have strong bones, a non-cemented prosthesis is used. In the case of the kneecap or patella, a circular piece of plastic is attached to its back allowing for the smooth and painless glide of the kneecap with bending and straightening of the knee. In the THR, the socket component or acetabulum is lined with either a durable cup of plastic, ceramic or metal. This lining usually eliminates the crepitus and pain that is so common in joints with Osteoarthritis (OA). In the TKR, a high-density polyethylene is used to replace the diseased or torn meniscus.

Advancement in surgical techniques, known as minimally invasive surgery (MIS), allows the physician to insert the total joint replacements through small incisions. Although not yet proven, it is hoped that MIS will allow for a quicker and a less painful recovery and hence a rapid return to normal activities.

Any prosthesis, just like a normal joint, develops wear and tear over time. Many things including patient’s body weight, age, high-impact activity levels, as well as, the implant’s weight-bearing surface can affect the longevity of the implant.

Generally, to be considered as a candidate for TJR, most physicians require the individual to meet the following criteria:3

- Pain severe enough to restrict work, recreation, and ordinary activities of daily living.

- Pain that is not relieved by more conservative methods of treatment, such as reduced activity, medication, rest or physical therapy.

- Significant joint stiffness.

- X-rays that show advanced arthritis or other degenerative problems.

What the Somatic Practitioner/Teacher should know about Total Joint Replacement

Movement and activity is a critical component, particularly during the first eight weeks, following a TJR. If fact most people are able to resume most normal light activities of daily living:

- Simple meal preparation, dusting, or washing the dishes

- Graduated walking program

- Normal household activities, with the exception of vacuuming, making the bed, mopping the floors or lifting heavy laundry

- Sitting with restrictions, standing, walking up and down stairs

- Specific exercises to restore movement and strength

After eight weeks usually a person is approximately 80% recovered. Most of their pain is gone but muscular weakness can still persist. Even though full recovery typically takes six months, by 12 weeks, most people are returned to full activity, including driving; but they are still encouraged to be aware of certain medical considerations such as blood clots and joint positions that compromise or increase vulnerability to instability or dislocation. Because of the differences between the underlying joint structure, surrounding musculature and the amount of deep tissue structures that must be cut through in the hip, the hip is particularly vulnerable. See section below titled Specifics on Total Hip Replacement and Hip Dislocation for more information. The knee is much less prone to post surgical injury.

Blood clots in the leg veins, pelvis or lungs are usually not a common ongoing complication of TJR. However, it is if the student/client has an underlying medical problem such as, chronic heart problems, history of a stroke, deep vein thrombus (DVT) or pulmonary embolism. They may be on blood thinner medication such as Coumadin, Plavix or aspirin. For your information, warning signs of possible blood clots include:4

- Pain in the calf and leg, unrelated to the incision

- Tenderness or redness of the calf

- Swelling of the thigh, calf, ankle or foot

- Shortness of breath

- Chest pain, particularly with breathing.

As a teacher, one should be aware that once a person has had a blood clot, they are typically prone to develop future clots. Most people have been educated by their physician on the various measures of blood clot prevention such as wearing special support hose, performing ankle pump exercises and the use of blood thinner medication.

Certain activities may lead to damage of the artificial joint over time due to wear and tear. In general, the more vigorous the activity, the higher the risk of damaging the prosthesis. Therefore, patients are counseled to avoid certain activities and sports for the rest of their life. These include:5

- Running and Jogging

- Certain team sports such as singles tennis, football, basketball, racquetball

- High‐impact aerobics

- Jumping

- Skiing

- Moving and lifting heavy objects

As a teacher, one should be aware that once a person has had a blood clot, they are typically prone to develop future clots. Most people have been educated by their physician on the various measures of blood clot prevention such as wearing special support hose, performing ankle pump exercises and the use of blood thinner medication.

Certain activities may lead to damage of the artificial joint over time due to wear and tear. In general, the more vigorous the activity, the higher the risk of damaging the prosthesis. Therefore, patients are counseled to avoid certain activities and sports for the rest of their life. These include:5

- Running and Jogging

- Certain team sports such as singles tennis, football, basketball, racquetball

- High‐impact aerobics

- Jumping

- Skiing

- Moving and lifting heavy objects

Specifics on Total Hip Replacement and Hip Dislocation

To understand the underlying challenges in a Total Hip Replacement (THR), it is helpful if we begin with the most problematic post-surgical complication-hip dislocation. The risk for dislocation is highest in the first two months after surgery.6

The hip is a ball-and-socket joint with the ball-shaped head of the femur fitting inside the cup-shaped socket of the pelvis. The structure of a ball-and-socket joint gives it a great deal of stability and yet, allows it to move freely. Generally, a great amount of force is required to pop the thighbone out of its socket, but that’s just what happens in a hip dislocation.

A hip dislocation occurs when the head of the thighbone (femur) slips out of its socket in the hip bone (pelvis). Approximately 90% of the time, the thighbone is pushed out of its socket in a backwards direction (posterior dislocation).7 This leaves the hip in a fixed position that is observed as bent (flexed) with the femur twisted inward and the knee pointing toward the middle of the body. The thighbone can also slip out of its socket in a forward direction (anterior dislocation). If this occurs, the hip will be only slightly bent, and the femur will twist outward and the knee will point away from the middle of the body.

A hip dislocation is very painful and a person is unable to move their leg. If there is nerve damage, they may not have any feeling in the foot or ankle area. In people without a THR, motor vehicle accidents are the most common cause of hip dislocations.

A hip dislocation is very painful and a person is unable to move their leg. If there is nerve damage, they may not have any feeling in the foot or ankle area. In people without a THR, motor vehicle accidents are the most common cause of hip dislocations.

The Connection Between THR and Dislocation

In people with THR, there are several factors that can influence a hip dislocation. These include: the type of surgical procedure performed, bone and musculature strength, and a person’s lifestyle. In the Traditional Hip Replacement procedure, a 10-12 inch incision is made over the posteriolateral, i.e. outer side of the thigh, closer to the back of the thigh. (Posterior means rear and lateral means side.)

With this large incision, there is more disruption of the muscles (small hip rotator muscles are cut) as well as tissues (iliotibial band or IT Band) of the leg. Not only is more time needed in healing but this disturbance can make the joint more vulnerable when placed in certain positions because of decreased stability.

Another surgical procedure is called the Anterior Approach Total Hip Replacement (THR). From an anatomical perspective, the hip joint is closest to the skin at the front of the hip and the muscle and fat layers are thinner than the muscle and fat tissue encountered on the side or rear of the thigh.

Using an incision on the front (anterior) of the thigh, along with x-ray imaging and a specially engineered table, the deteriorated hip is replaced sparring any detachment of muscles or tendons from the bone.8 Working in between the muscles and keeping them intact reduces trauma and post-operative pain, providing greater hip stability immediately after surgery and potentially lowering the risk of dislocation. Additionally, the Anterior Approach impacts the overall time it takes to heal from surgery, and in the following post-op years, aids to further prevent dislocations.

A relatively new surgical procedure being offered to people today is called the Minimally Invasive Surgery (MIS) Total Hip Replacement.

You can view this surgical animation in our on-line library. As its name suggest, the goal of this procedure is to minimize the amount of soft tissue damage that occurs in a THR. One or two small incisions, generally 2-4 inches, are used rather than the traditional 10-12 inch incision. With two incisions, one is made nearer the front of the thigh and is used to prepare and insert the new socket prosthesis. The second incision is made toward the back of the thigh and is used to prepare and insert the stem or ball portion of the prosthesis.9

Whichever type of surgical procedure, any person with a Total Hip Replacement (THR) is instructed to take additional precautions initially. This is especially critical for the first year post-op for someone who underwent the Traditional Hip Replacement. Awareness is the key to prevent, usually posterior, dislocation of the prosthesis. These include:10

- Not crossing the legs either at the ankles or knees in sitting or when lying on the back. It is important to keep the feet six inches apart when sitting.

- Not bending the hips more than a right angle (90 degrees) in sitting on a chair, toilet seat, or bathtub,(hips/pelvis higher than knees), standing (bending over and touching the floor or tying shoes) or when lying on the back (bringing knees to the chest).

- Sit with the back straight. Do not lean forward allowing the shoulders to go in front of the hips.

- Not turning the feet/knees excessively inward or outward.

- Use of a pillow between the legs at night when sleeping.

- Avoid sexual activity for the first six to eight weeks.

According to The Center for Hip and Knee Surgery, lifetime restrictions for a person with a THR, primarily, the Traditional Hip Replacement procedure (posteriolateral approach) include:11

- Do not twist the operated leg inward with quick or exaggerated movements.

- Do not pivot when standing. Instead, take small steps to turn around. Also, avoid planting the feet in one spot and turning against the hip in either direction.

- Do not turn and reach behind oneself.

- Do not jerk the operated leg. For example, if your foot is stuck in mud, do not forcefully pull it out. Take the foot out of the shoe and let someone else pull the shoe out of the mud.

- Do not lift and carry anything that weighs more than 20 pounds. If you lift 20 pounds, the amount of weight your hips are supporting is approximately 60 pounds. This is too much stress for an artificial hip joint. Some objects that might be too heavy to lift include: groceries, laundry, garbage, toolboxes, children, pets, luggage, golf bags, and bowling balls. The idea includes one’s own body weight.

- Do not participate in sports that require any jumping.

What the Somatic Practitioner/Teacher should know about THR

Because of advancements in surgical procedures, attention to precautions and contraindications should be done on an individual basis. Not all students in your class may be informed of their lifetime restrictions or the surgical procedure they underwent, let alone the physician’s individual practice guidelines.

As with any student in your class that has had a surgical history involving the spine or peripheral joints, the Somatic Practitioner needs to know their own professional limitations and scope of practice. Somatic Education practices such as the Bones For Life Program® or the Feldenkrais Method of Movement® can be used safely and contributes immensely to efficient and functional return to activities of daily living as well as restoring the emotional freedom that had been blocked because of pain and dysfunction.

- How long ago was the hip replacement? Is the client aware of any lifetime activity restrictions? Has the client been released by their doctor for full range of motion and return to their full activity level? If so, get a clear list. Sometimes clients will say yes, but then when asked if they are allowed to get up and down from the floor will indicate they are not allowed to bend down to pick items up from the floor, especially within the first eight weeks of surgery

- Even after the first year of avoidance of specific positions of the joint that could lead to dislocation. Understanding the surgical entry point (anterior or posterior) can help you help the client track safe movements. If the entry point was posterior, then movements such as taking the knee toward the chest coupled with movement towards the body mid‐line creates more risk of dislocating the ball from the socket since it puts pressure on the tissue that was recently cut. If the entry point was anterior, opening the knee (frog‐leg position) away from the mid‐line and more extended creates more risk. This can be valuable to know, not only in specific exercises/movements, but also in mapping out functional activities such as coming to stand.

- Do not assume that the person will be able to track safe movement in their affected joint by monitoring their own comfort. When one has an artificial joint, there is loss of the sensory information in that joint because of the musculotendons that have been cut and the proprioceptive and pain receptor information they once provided is no more or is distorted. Therefore, it is not easy to know when one has gone too far as tissue damage can occur long before any feeling of discomfort is noticed.

- If your practice/class involves work on the floor, does this person currently get up and down from the floor?

- When teaching some such as a spiral up to stand from a chair or the floor, spend time coaching light‐easy pivoting on the feet. There can be a tendency to stay static on the foot which is why the lifetime restriction of “No pivoting in standing” is given to individuals with THR in the first place. This static positioning can be quite damaging to tissue that is still healing and even reduce the life of the artificial joint.

- A person wanting to enroll and participate in a class may be long dismissed from their doctor’s care. If they already have an easy range of motion with no concerns on their or their doctorʹs part, great. However, if they cannot open or close the hip joint easily in any specific direction, working with them within the available range can be more advantageous; thus, coaching them to avoid the trap of ʺtrying to increase range of motionʺ that students and teachers sometimes fall into. Again small improvements will be beneficial adding to an overall contribution of other joints and a sense of proportional flexibility. Large improvements in local joint range of motion may not yield valuable results and even contraindicated.

What Somatic Education Offers Individuals with TJR

While most people will be instructed to participate in a light exercise program, the somatic teacher can help immensely during all phases of the Total Joint Replacement rehabilitation by constructing lessons that:

- reorganize and retrain the affected hip, leg, and spine into the person’s overall movement patterns. The surgical procedure permanently alters the once organic and normal mechanics of that joint(s). For example, with either THR approach and with TKR, the gluteal (buttocks) muscles are weakened. Even with good physical/occupational therapy they often remain weak in the functional use of those muscles.

- build and advance the person’s awareness in discovering how activation of deeper muscles and tissue structures in adjacent areas can contribute to an overall better quality of function. Sadly enough, this activation may have never been available, even prior to surgery, and may have been one of the contributing factors to the deterioration of the joint in the first place. In the Feldenkrais Method® there are many key lessons in activating the gluteal and quadriceps muscles in ways seldom seen in any other rehab, movement or exercise approach. Refocusing from gross muscle development to a finer level will serve the person with a TJR extremely well.

- confront and enhance a person’s ability to recover from challenges in balance. Here, the Bones for Life® program has a tremendous palate from which to choose, including processes that enhance proportional flexibility.

In summary, somatic educational approaches expand avenues of pain-free movement as well aid in the integration of all parts of the person into a whole. The ways in which these approaches coach balance from the foot, ankle, ribs and cervical spine is unique. Furthermore, it is possible that their additional contribution may be in preventing the need for TJR in the first place and if one is needed; it also may extend the life of the new joint beyond the traditional 10-year mark.

Carol Montgomery is a Physical Therapist, Guild Certified Feldenkrais Practitionercm and Bones for Life® Teacher/Trainer. She has a private practice in Columbus, IN. Montgomery can be reached by email at camontgomery11@yahoo.com. Montgomery offers certification and continuing education programs through www.integrativelearningcenter.org.

References

- National Center for Health Statistics; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2003 National Hospital Discharge Survey.

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons: www.AAOS.org.

- Costal Orthopedics and Sports Medicine. Computer‐Assisted Total Knee Replacement Surgery. Bradenton, FL. 2007.

- Columbus Regional Hospital. Patient Education Handout. Columbus, IN. 2007.

- Columbus Regional Hospital. TJR Patient Education Handouts. Columbus, IN. 2006.

- The Center for Hip and Knee Surgery. Patient Education Handout. Mooresville, IN. 2005.

- Ibid. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.

- Ibid. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.

- Ibid. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.

- Columbus Regional Hospital. TJR Patient Education Handouts. Columbus, IN. 2006.

- Ibid. The Center for Hip and Knee Surgery.